The $1.7 Trillion Question

The paradox of modern higher education is as sharp as it is expensive. For generations, a college degree has been sold as the quintessential key to a better life, the most reliable pathway to economic mobility, intellectual enrichment, and professional security. Yet, today, that key comes at a cost that is crushing the very people it is meant to uplift. In the United States alone, more than 43 million borrowers collectively owe an astonishing $1.77 trillion in student loan debt, a figure that looms over the national economy like a storm cloud.[1] This financial burden has transformed a rite of passage into a decades-long sentence of repayment for millions.

This situation forces a series of critical questions.

- How did the university, an institution born from the noble mission to preserve, create, and transmit human knowledge, morph into a high-stakes, debt-financed consumer product?

- What happened along the way to turn seats of learning into engines of commerce?

- And perhaps most unsettlingly, as the price of admission has soared into the stratosphere, why does the prize itself, the degree, seem to offer less of a guarantee than ever before?

Graduates are increasingly finding themselves underemployed, working in jobs that don’t require their expensive credentials, and facing a labor market that questions the value of their skills.

Let’s trace the long, complex, and often contradictory history of the university to answer these questions. The journey begins in the ancient world, where the first centers of higher learning emerged to serve gods, kings, and scholars. It moves through the Middle Ages and the Enlightenment, which forged the university’s identity as both a sanctuary for knowledge and a tool for public good. It will then pinpoint the critical turning points in the 20th century, particularly in the American system, where a series of policy decisions, economic shifts, and cultural changes began to unravel the post-war consensus of education as a publicly funded right. Finally, we will analyze the consequences of this transformation: a high-cost, market-driven system that has created a profound and painful paradox of value for today’s students.

This is the story of how the ivory tower was put up for sale, and why we are paying the price.

1 - The Ancient Origins of the University

The roots of higher education are intertwined with the very dawn of human civilization and the specialization of labor. As societies grew more complex, the need arose for a class of individuals dedicated not to farming or fighting, but to preserving and advancing knowledge. These were the first scribes, priests, administrators, and thinkers, and the institutions that trained them were the primordial ancestors of the modern university.

The Dawn of Specialized Knowledge

In ancient Mesopotamia, the development of the complex cuneiform writing system necessitated formal training. Only a select few were chosen to become scribes, typically the sons of royalty and professionals like physicians and temple administrators.[2] These scribal schools, known as edubas, were centers where literacy was disseminated among the elite from as early as 2000 BCE.[2] The curriculum was rigorous, involving the mastery of vocabularies, grammars, and the extinct Sumerian language.

In ancient Egypt, a similar system prevailed. Literacy was concentrated within an educated elite of scribes who served pharaohs, temples, and the military.[2] The hieroglyphic system was deliberately kept difficult to learn, preserving the scribes’ exclusive status. In these early societies, knowledge was not a public good but a carefully guarded instrument of state and religious power.

Global Roots of Higher Learning

Long before the first European universities took shape, vibrant centers of higher learning flourished across the globe, typically sponsored by royal courts, religious institutions, or scientific bodies.[3] These institutions demonstrate that the impulse to create formal spaces for advanced study is a universal one.

In Asia, the Indian subcontinent was home to great Buddhist monastic universities, or mahaviharas. Among the most famous were Nalanda and Taxila. Nalanda, a renowned center for Buddhist scholarship, attracted thousands of students and scholars from across Asia, including China, Persia, and the Middle East.[3] Taxila, which may date back to the 6th century BCE, offered a remarkably diverse curriculum. Students entering at age sixteen could study the sacred Vedas alongside the “Eighteen Arts,” which included practical skills like archery, hunting, medicine, and military science.[3] This early blend of religious, liberal, and vocational training shows that the debate over the purpose of education is ancient indeed.

In the Middle East, Al-Azhar was established in Cairo in 970 CE by the Fatimid Caliphate.[5] Initially a madrasa, or Islamic school, it taught the Qur’an, Islamic law, theology, Arabic grammar, and logic.[5] For much of its early history, its structure was informal, with no entrance requirements, formal curriculum, or degrees, emphasizing a model of scholarly mentorship over credentialing.[5]

In classical Europe, Plato’s Academy, founded in Athens around 387 BCE, served as a center for the study of philosophy and mathematics.[3] In Ptolemaic Egypt, the great Museum and Library of Alexandria functioned as premier organizations of higher learning, drawing scholars from across the Hellenistic world.[3]

The Birth of the European University

The direct lineage of the modern Western university began in medieval Europe. Institutions like the University of Bologna (established in 1088), the University of Paris, the University of Oxford (with evidence of teaching in 1096), and the University of Cambridge (founded c. 1209) evolved from pre-existing cathedral and monastic schools that originally trained clergy.[3]

A pivotal development in this evolution was the rise of academic guilds. As the demand for education grew, professional teachers began to organize themselves into corporations, or universitas, to gain control over their curriculum and attract fee-paying students.[7] This marked a crucial, early shift of power away from the exclusive control of the Church and into the hands of the educators themselves, forming the basis of the primitive university.[7]

The University of Oxford provides a clear case study of this new model’s development and funding. Its growth accelerated dramatically after 1167, when King Henry II, in a political dispute with the Archbishop of Canterbury, banned English students from attending the University of Paris.[9] Many of these returning scholars and students settled in Oxford. Initially, the university was simply a collection of masters and students who lodged with the townspeople. This arrangement led to frequent and often violent clashes between “town and gown”.[9] These riots hastened the establishment of endowed halls of residence, which evolved into the first colleges. University, Balliol, and Merton Colleges, established between 1249 and 1264, were founded not by the state, but by wealthy patrons and churchmen like William of Durham.[9] These colleges were self-governing entities with their own buildings and, crucially, their own endowments, primarily in the form of land and later, investments.[10] This established a funding model based on private wealth and patronage, one that allowed institutions like Oxford and Cambridge to operate for centuries without needing state aid or relying on mass tuition fees.[12]

The early curriculum was standardized around the seven liberal arts, grammar, rhetoric, logic, arithmetic, geometry, astronomy, and music, which formed the basis of the Arts faculty.[10] Students could then proceed to the higher faculties of Law (both Civil and Canon), Medicine, and Theology.[7]

From these diverse origins, a fundamental tension emerges that remains at the heart of higher education today. On one hand, there is the “public utility” model, where institutions are sponsored by rulers and states to serve practical ends. The scribal schools of Mesopotamia, Charlemagne’s palace schools designed to train aristocrats to manage their lands 4, and the military science taught at Taxila 3 all exemplify this approach. On the other hand, there is the “scholarly sanctuary” model, where institutions are sponsored by religious orders or patrons to preserve philosophical or theological truth, largely for its own sake. Plato’s Academy, the Buddhist scholarship of Nalanda 4, and the theological focus of the early European cathedral schools fit this mold. The modern debate over whether a university should primarily provide job skills or a broad liberal arts education is not a new dilemma. It is a continuation of a conflict embedded in the very DNA of higher learning. The story of the university is not a simple shift from a “pure” mission to a “commercialized” one, but rather a dramatic and ongoing struggle over which of these ancient purposes should dominate and, most importantly, who should pay for it.

2 - A Great Transformation: From Divine Right to Public Good

For centuries, the university remained a relatively static institution, serving the church and the aristocracy. Its purpose was to train a small elite in theology, law, and the classics, funded by endowments and patronage. However, two major historical shifts, the Enlightenment and the post-World War II democratic expansion, radically transformed this model, recasting the university from a private privilege into a public good and an engine of national progress.

The Enlightenment and the University of Reason

The 18th-century intellectual movement known as the Enlightenment, or the Age of Reason, sparked the first major philosophical overhaul of the university. Thinkers like Immanuel Kant, John Locke, and Voltaire championed reason, science, and individualism, challenging the university’s traditional role as a bastion of religious dogma and inherited authority.[13]

This intellectual shift had profound structural consequences. As national legal systems emerged and replaced feudal laws, the governance of universities began to move from the authority of the Church to the control of the state.[13] National ministries of education were formed to oversee university policies, creating a more centralized and secular system. The curriculum was modernized to reflect the new emphasis on empirical knowledge and critical inquiry. Subjects like mathematics, natural sciences, and modern philosophy gained prominence, pushing aside the singular focus on theology.[13]

The most influential expression of this new ideal was the Humboldtian model of higher education, which emerged in Germany in the early 19th century.[14] Spearheaded by the philosopher and statesman Wilhelm von Humboldt, this model was revolutionary. Its core principle was the unity of research and teaching (Einheit von Forschung und Lehre), arguing that students learn best when they are engaged with the process of discovery alongside their professors.[14] The Humboldtian ideal championed unconditional academic freedom, insisting that universities must be independent from the ideological, economic, and political influence of the state.[14] To ensure this independence, Humboldt even proposed that universities should possess their own assets and goods to finance themselves.[14] The ultimate goal was not merely to train students for a profession, but to cultivate them through a broad, humanistic education (Bildung) into autonomous individuals and critical-thinking “world citizens”.[14] This powerful vision of the research-based, academically free university became the blueprint for modern higher education institutions across Europe and, eventually, the world.

The American Experiment: Democratizing the Ivory Tower

While the European model was being philosophically refined, the United States embarked on a radical experiment to democratize it. The American vision saw higher education not just as a place for elite intellectual cultivation but as a practical tool for national development and social mobility.

A pivotal moment in this process was the passage of the Morrill Land-Grant Acts of 1862 and 1890.[15] These acts donated federal lands to the states for the purpose of establishing colleges. Critically, the mission of these new institutions was to teach practical subjects such as “agriculture and the mechanic arts,” alongside scientific and classical studies, in order to “promote the liberal and practical education of the industrial classes”.[15] This was a deliberate break from the classical, elite model of Harvard and Yale, cementing the idea of the university as a public good designed to serve a broad cross-section of the population.

However, the single most transformative event in the history of American higher education was the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944, universally known as the G.I. Bill. The Second World War had financially devastated many smaller private colleges, which saw their male student bodies vanish into the armed forces.[17] The G.I. Bill reversed this trend in a spectacular fashion. It provided federal funding to cover tuition and living expenses for over 2.2 million returning veterans to attend college.[18] The impact was immediate and staggering. Total college enrollment in the U.S. jumped by more than 50%, from 1.3 million in 1939 to over 2 million in 1946.[18] An institution that had once been the exclusive domain of the wealthy elite was suddenly flooded with students from every social and economic background. The G.I. Bill single-handedly created the American middle class of the mid-20th century and firmly established the principle that the federal government had a vital role to play in ensuring access to higher education.

Yet, embedded within this celebrated act of public investment was a mechanism that would have profound and unforeseen consequences decades later. The G.I. Bill did not provide block grants directly to universities to lower their costs for everyone. Instead, it operated as a massive voucher-like system, giving money directly to the veterans to spend at the institution of their choice. This approach, while noble in its goal of providing individual choice and opportunity, subtly but powerfully reframed the relationship between student and institution. It created, for the first time, a mass consumer market for higher education. Universities now had to compete for a huge new pool of customers who arrived with federal money in hand. This student-centric funding model, which treated federal aid as a portable subsidy that followed the individual, established the very market dynamics that would later be exploited. It laid the institutional and psychological groundwork for the loan-based system to come, a system where universities could raise prices with the knowledge that federal aid, in one form or another, would expand to help students meet the cost. The greatest act of public investment in higher education inadvertently planted the seeds of its future privatization.

3 - The Turning Point: How the Noble Mission Became a Business Model

The post-war era, fueled by the G.I. Bill and robust public investment, represented the high-water mark of the university as a public good in the United States. Tuition at public universities was low, often nominal, and a college degree became the central pillar of the American Dream. But beginning in the latter part of the 20th century, a series of interconnected forces converged to dismantle this model. This was the critical turning point, the moment the university’s noble mission was subsumed by a new, market-driven business model. This section dissects the mechanisms that drove this transformation and commercialized American higher education.

The Great State Defunding

The foundation of the affordable public university system was the financial commitment of state governments. For decades, states viewed higher education as a wise public investment, and their appropriations covered the lion’s share of institutional operating costs. However, starting in the 1980s and accelerating over the following decades, this commitment began to erode. On a per-student basis, state funding for higher education entered a long and steady decline.[19]

This shift was not born of a single cause but a confluence of pressures. State budgets were squeezed by rising costs in other areas, particularly Medicaid, which competed for the same pool of public funds.[1] This was compounded by a broader political and ideological shift that began to reframe higher education not as a public good that benefits all of society, but as a private benefit that primarily enriches the individual graduate.

If the benefit was private, the logic went, then the cost should be borne by the individual as well.

This ideological change made cutting higher education budgets more politically palatable than raising taxes or cutting other services. As state funding dwindled, public universities, which educate the vast majority of American students, were left with a massive revenue gap. To survive and grow, they had to look for money elsewhere.[1]

The Crucial Pivot: From Grants to Loans

The federal government’s response to this growing affordability crisis was the single most important factor in the privatization of higher education. Instead of filling the gap left by states with direct institutional funding, which would have kept tuition low, policymakers made a fateful choice. The Higher Education Act of 1965, and the programs that followed, created a system of federally guaranteed student loans, initially provided by private banks and lenders through the Federal Family Education Loan (FFEL) program.[15]

This was a deliberate policy decision. Creating a loan program was seen as more politically and budgetarily attractive than direct federal spending, as the full cost of direct grants would appear on the federal budget immediately.[15] The loan system, by contrast, created a vast new pool of capital for students to borrow, effectively shifting the financial burden from the government to the individual student.

This flood of available loan money had a predictable, and now well-documented, effect on college pricing. In 1987, then-Secretary of Education William Bennett articulated what came to be known as:

the “Bennett Hypothesis”: The ready availability of federal financial aid enabled colleges and universities to “blithely raise their tuitions,” confident that students could simply borrow more to cover the escalating costs.[22]

While the exact mechanics are debated, research confirms the core of this dynamic. The “pass-through rate”, the amount by which tuition increases for every dollar of new aid available, has been a significant driver of tuition inflation.[22] When loan limits were tight and students were credit-constrained, this effect was particularly strong. After major expansions of loan programs, such as the introduction of unsubsidized loans in 1993 and another large expansion in 2008, the immediate effect on tuition temporarily slowed, as students were no longer as constrained. However, as inflation and other cost pressures inevitably rose over time, students once again became constrained, and the upward pressure on tuition resumed. This created a powerful ratchet effect, with each expansion of federal lending enabling another round of tuition hikes.[22]

The Campus “Amenities Arms Race”

With declining state support and a new, seemingly endless revenue stream from federally backed student loans, universities began to compete for students not just as scholars, but as customers. This ignited what has been termed the “amenities arms race”.[23] To attract the tuition dollars of 18-year-olds (and their parents), institutions began pouring money into lavish, non-academic facilities.

Campuses were transformed with resort-style dormitories, massive recreation centers with rock-climbing walls, and opulent student unions. North Carolina State University, for example, undertook a $120 million renovation of its Talley Student Union, funded by a new, mandatory student fee of nearly $300 per year.[23] High Point University, a small private school, has spent over $700 million since 2005 to refurbish its campus, financed largely by borrowing and student fees.[23] This spending extends to state-of-the-art gyms and ever-larger football stadiums, which serve more as marketing tools than educational facilities.[19] Research indicates that this focus on amenities is a direct response to market demand, particularly from wealthier students with lower academic aptitude, who show the strongest preference for recreational facilities over academic quality.[23] The immense cost of this arms race is passed directly on to all students in the form of higher tuition and fees.

Administrative Bloat and the Corporate University

As universities began to operate more like businesses competing in a marketplace, their internal structures changed accordingly. The most dramatic shift was the explosion in the number of non-teaching administrative staff.[19] The ranks of fundraisers, marketers, admissions officers, alumni relations staff, wellness counselors, and diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) officers swelled, growing at a rate that far outpaced the growth of full-time faculty.[20]

This “administrative bloat” reflects a fundamental change in institutional priorities. A significant portion of the university’s budget is now dedicated to non-academic functions like student recruitment, brand management, and providing an ever-expanding array of student support services.[20] This shift towards a corporate management model has also been accompanied by a sharp rise in executive-level salaries for top administrators, adding to the immense overhead costs that are ultimately funded by student tuition.[19]

A Tale of Two Systems: The European Counterpoint

It is crucial to recognize that the high-tuition, high-debt model that defines American higher education was the result of specific policy choices, not an economic inevitability. A brief look at the systems in place across Europe reveals a profoundly different philosophy and approach.

- Germany: Higher education is viewed as a public good and is funded almost entirely by the state. Nearly 90% of university funding comes from government sources, with the individual federal states providing the bulk of the basic funding.[24] As a result, tuition at public universities is generally free for all students, including internationals.[26]

- France: The French state is the primary funder of higher education, heavily subsidizing its public universities.[28] The true cost of educating a student is estimated to be around €10,000 per year, but the government assumes the vast majority of this cost. This allows public universities to charge exceptionally low tuition fees, for example, around €175 per year for a bachelor’s degree for EU students.[29]

- Scandinavia: The Nordic model is built on social democratic principles, viewing higher education as a pillar of the welfare state and a right for all citizens.[31] These systems are characterized by high levels of public funding and, consequently, no or very low tuition fees.[31] In countries like Norway and Sweden, higher education is tuition-free for students from within the EU/EEA.[33]

These examples demonstrate that maintaining an accessible, affordable, and high-quality system of higher education is a matter of political will and societal priority. The American system’s trajectory was not preordained. It was the outcome of a fundamental philosophical shift in which the financial risk of higher education was deliberately transferred from the collective, the state, to the individual student. The student loan system was not merely a financial tool; it was the primary instrument for executing this transfer. This act had profound consequences, transforming students into debt-fueled consumers and universities into service providers competing for market share. The university was no longer just a public institution accountable to the state for the public good; it had become a privatized service accountable to the market for its bottom line.

4 - The Paradox of Value: A Degree is More Important, and Worth Less, Than Ever

The commercialization of the university has created a deeply paradoxical situation for today’s graduates. On one hand, a college degree is more essential than ever, a non-negotiable ticket to entry for most professional careers. On the other hand, the value of that ticket has become increasingly uncertain and variable. The high-cost, high-debt system has flooded the market with credentials, leading to degree inflation, widespread underemployment, and a growing mismatch between the skills graduates possess and the skills employers demand. This is the ultimate consequence of the university’s transformation: a system that promises a premium return on investment but often delivers a precarious foothold in the modern economy.

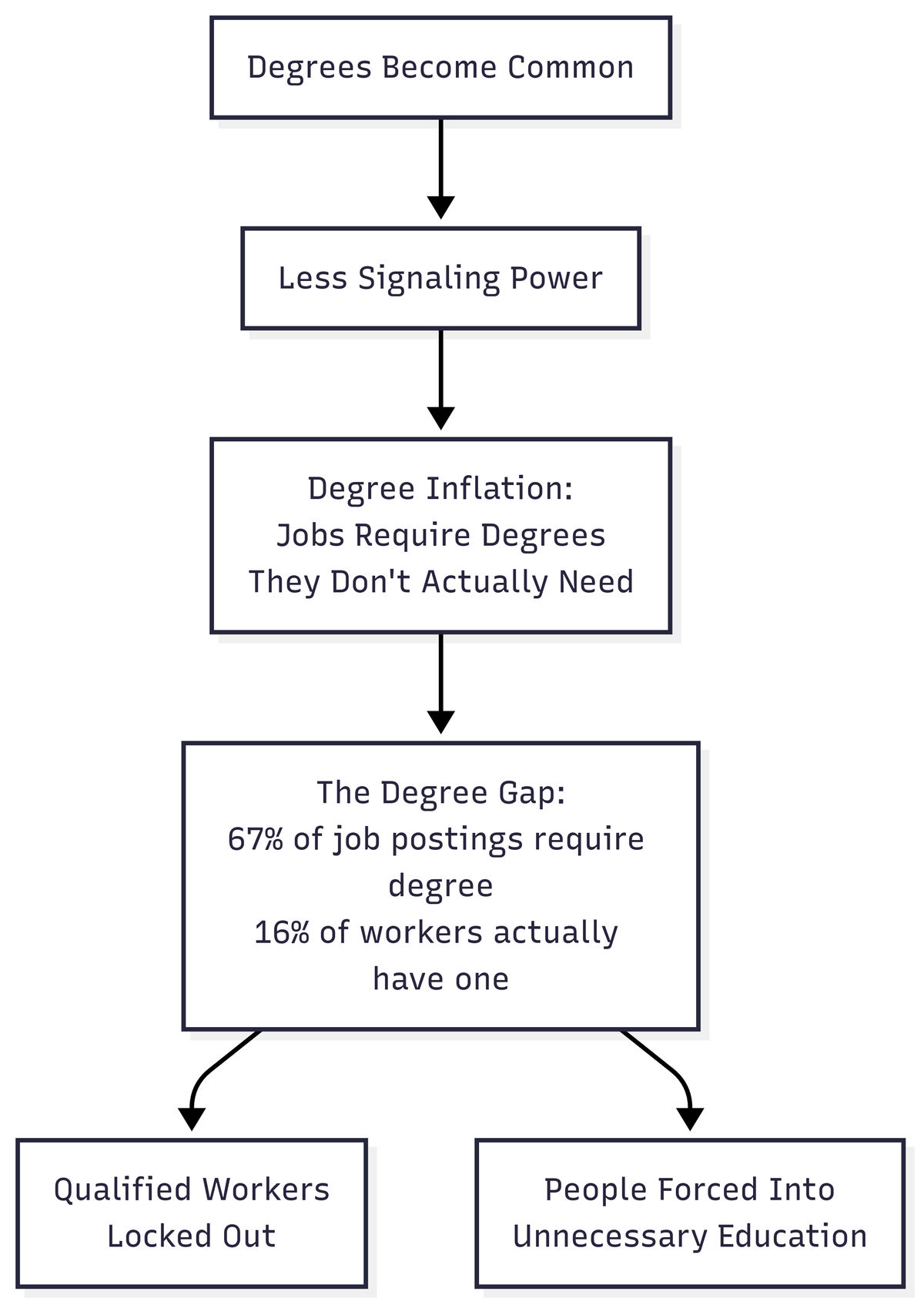

Degree Inflation and the Credential Society

As a bachelor’s degree shifted from an elite distinction to a mainstream expectation, its signaling power in the labor market diminished. In response, employers began requiring a four-year degree for jobs that had never needed one before, a phenomenon known as “degree inflation”.[36] This practice is often less about a genuine increase in the skills required for a position and more about using the degree as a convenient screening tool to filter a vast pool of applicants.[37]

This has created a significant “degree gap” in the workforce. A 2015 analysis found that while 67% of job postings for production supervisors required a bachelor’s degree, only 16% of the people actually employed in that role held one.[38] This trend has corrosive effects. It locks millions of experienced and qualified workers without degrees out of opportunities for advancement and forces countless others into a costly and time-consuming educational path simply to be considered for jobs they are already capable of performing.[38] The degree becomes less a marker of acquired skill and more a minimum ticket to ride.[37]

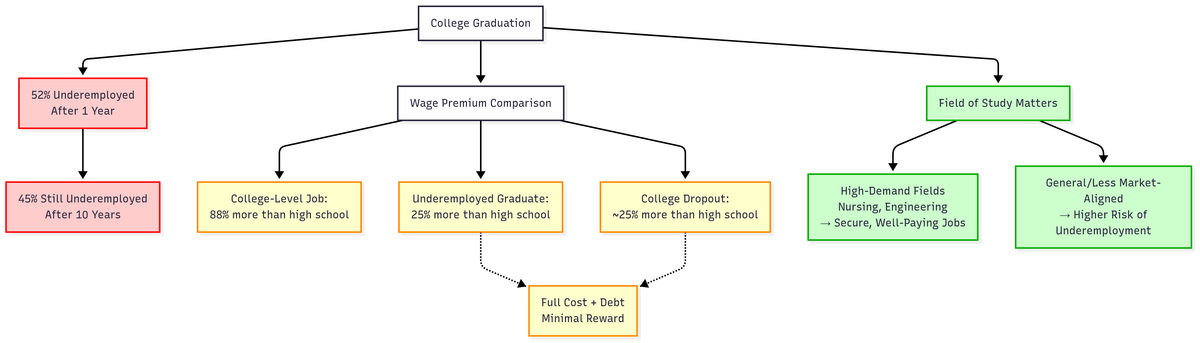

The Underemployment Crisis

The most direct and damaging evidence of the degree’s diminishing value is the staggering rate of underemployment among recent graduates. A landmark 2024 report found that 52% of college graduates are underemployed one year after graduation, meaning they are working in jobs that do not typically require a college degree.[37] This is not a temporary phase of “paying one’s dues.” The problem is remarkably persistent: ten years after graduation, 45% of these individuals are still underemployed.[39]

This has devastating financial consequences. The much-touted “college wage premium” largely evaporates for the underemployed. A recent graduate working in a college-level job earns, on average, 88% more than a high school graduate. By contrast, an underemployed recent graduate earns only 25% more, roughly the same as someone who attended college but dropped out.[39] They have incurred the full cost and debt of a degree but are reaping little of its promised economic reward.

Crucially, the value of a degree is no longer monolithic; it has fractured, with outcomes now varying dramatically by field of study. A degree in a high-demand, specialized field like nursing or engineering provides a much more direct and secure path to a well-paying job than a degree in a more general or less market-aligned field.

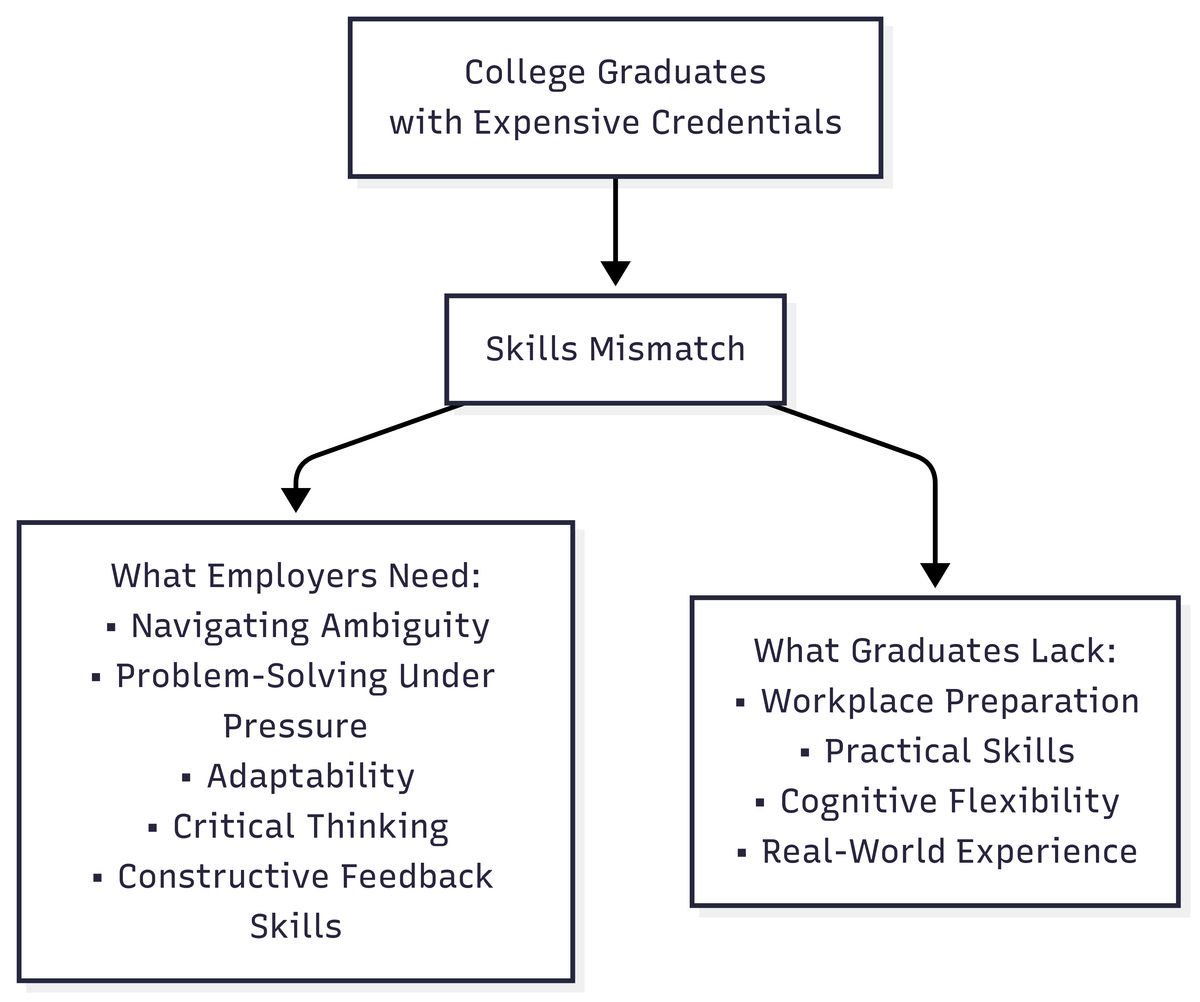

The Skills Mismatch

Compounding the problem of underemployment is a persistent complaint from the business community: that college graduates, despite their expensive credentials, are often unprepared for the realities of the modern workplace. A significant gap exists between the skills employers seek and the qualifications of recent graduates.[45]

The most cited deficiencies are not in technical, job-specific skills, but in what are often called “durable” or “soft” skills. A 2025 report based on insights from early-career employees found a pressing need for stronger preparation in areas such as navigating ambiguity, problem-solving under pressure, adaptability, critical thinking, and the ability to give and receive constructive feedback.[45] This suggests that while universities are effective at issuing credentials, they are struggling to cultivate the practical and cognitive flexibility required in a rapidly changing economy.

The 2025 Labor Market Reversal

The culmination of these trends has been a recent and alarming reversal in the labor market. For decades, a core tenet of economic wisdom was that college graduates enjoyed significantly lower unemployment rates than the general population. In 2025, that historical trend inverted.

In March 2025, the unemployment rate for college graduates aged 22-27 hit 5.8%, while the overall national unemployment rate was just 4.2%, the largest such gap in over 30 years.[37] By May 2025, the rate for recent bachelor’s degree holders had climbed to 6.1%, and for those with advanced degrees, it reached an even more startling 7.2%.[48] This deterioration in job conditions has been particularly sharp for recent graduates compared to older, more established workers, and it has been concentrated in white-collar occupations like computer science, media, and design.[49] This suggests that the traditional security offered by a degree, especially at the point of entry into the workforce, is weakening in a way not seen in modern history.

This complex reality reveals that the “value of a college degree” has fractured into distinct components. There is the Economic Value, which provides a direct and high return on investment, but as the data shows, is now largely confined to specific, high-demand majors. There is the Credential Value, which serves as the necessary “ticket to ride” but does not guarantee a good job or a commensurate salary. And there is the Intrinsic Value, the personal growth, critical thinking, and intellectual expansion that has always been a part of the university’s promise.[51]

The current crisis stems from a profound misalignment of these values. Students are taking on unprecedented levels of debt with the expectation of receiving clear Economic Value. The university system, in its marketing and mission statements, often sells a combination of Economic and Intrinsic Value. However, for the 52% of graduates who find themselves underemployed, the labor market grants them only Credential Value, which is insufficient to justify the enormous financial risk they have undertaken. This disconnect between the price paid, the value promised, and the reality delivered is the very heart of the modern degree’s diminishing worth.

Conclusion: Reclaiming the University’s Promise

The journey of the university is a sweeping narrative of transformation. It began as a scattered collection of sacred and state-sponsored institutions, the exclusive domains of scribes, clerics, and aristocrats, funded by patrons and designed to preserve knowledge and power. It was reimagined during the Enlightenment and democratized in the post-war 20th century, becoming a state-funded engine of mass mobility and a cornerstone of the public good. But in recent decades, particularly in the United States, it has undergone another, more troubling transformation, devolving into a market-driven, debt-fueled credentialing service.

The critical turning point was the deliberate transfer of financial risk from the collective to the individual. As states withdrew public funding, the federal government stepped in not with direct support to keep costs low, but with a vast loan program that empowered students to borrow more. This single decision fundamentally altered the incentives for everyone. Universities, now competing for debt-financed tuition dollars, began to behave like corporations, pouring money into marketing and amenities while raising prices to signal prestige. Students, in turn, were recast as consumers, and their education became a product to be purchased on credit.

The consequences of this shift are now painfully clear. We have a system where the cost of attendance has become a barrier to the very social mobility it is supposed to provide.

We have a paradox where the bachelor’s degree has become both a mandatory credential for entry into the middle class and an increasingly unreliable investment, leaving millions of graduates underemployed and burdened by debt they cannot repay. The alarming recent trend of higher unemployment among recent graduates than the general population is a stark warning that the traditional college-to-career pipeline is faltering.

Reclaiming the university’s promise requires moving beyond incremental fixes and confronting a fundamental question of purpose. Is the primary role of higher education to supply the economy with job-ready workers, or is it to cultivate educated, critical citizens capable of navigating a complex world? The current system tries to be both and, for a growing number of its students, succeeds at neither. It charges a premium price for a vocational outcome it often fails to deliver, while the broader, intrinsic benefits of learning are sidelined in the desperate scramble for a return on investment.

The path forward is not a simple return to the past, but it does demand a conscious societal choice about what we value and how we are willing to fund that vision. The European models of heavily subsidized, low-tuition public education demonstrate that alternatives exist. A renewed commitment to higher education as a public good, an investment in our collective future rather than a private debt for individuals, is not a matter of nostalgia, but of necessity. The health of our economy, the strength of our democracy, and the promise of generational progress depend on it.

Acknowledgement

This work has utilized generative artificial intelligence, Gemini 2.5 Pro by Google, to assist with several aspects of the writing process, including locating references, brainstorming the outline, and paraphrasing.

Reference

- Recent Trends in the Cost of College Show the Continued …, accessed on September 3, 2025, https://www.americanprogress.org/article/recent-trends-in-the-cost-of-college-show-the-continued-importance-of-federal-and-state-investment/

- History of education - Wikipedia, accessed on September 3, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_education

- Ancient higher-learning institutions - Wikipedia, accessed on September 3, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ancient_higher-learning_institutions

- THE ORIGIN OF UNIVERSITIES, accessed on September 3, 2025, https://www.la.utexas.edu/users/bump/OriginUniversities.html

- Al-Azhar University | World University Rankings | THE - Times Higher Education (THE), accessed on September 3, 2025, https://www.timeshighereducation.com/world-university-rankings/al-azhar-university

- Al-Azhar University in Cairo, Egypt is the second oldest university in the world as it was first established in 972 CE under the Fatimid Caliphate | La Ligue Islamique Mondiale, accessed on September 3, 2025, https://themwl.org/fr/node/38876

- The Medieval University – Science, Technology, & Society: A Student-Led Exploration, accessed on September 3, 2025, https://pressbooks.pub/anne1/chapter/the-medieval-university/

- The Medieval University – Science Technology and Society a Student Led Exploration, accessed on September 3, 2025, https://opentextbooks.clemson.edu/sciencetechnologyandsociety/chapter/the-medieval-university/

- History - University of Oxford, accessed on September 3, 2025, https://www.ox.ac.uk/about/organisation/history

- A Short History of Oxford University, accessed on September 3, 2025, https://localhistories.org/a-brief-history-of-oxford-university/

- Oxford University: History, Traditions and Interesting Facts - YouTube, accessed on September 3, 2025, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EAfM52XY1t8

- University fees in historical perspective - History & Policy, accessed on September 3, 2025, https://historyandpolicy.org/policy-papers/papers/university-fees-in-historical-perspective/

- The Enlightenment and the Emergence of Modern Universities, accessed on September 3, 2025, https://www.universitylawtutors.co.uk/history-of-university-law-in-europe-enlightenment-and-the-rise-of-modern-universities

- Humboldtian model of higher education - Wikipedia, accessed on September 3, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Humboldtian_model_of_higher_education

- American Higher Education’s Past Was Gilded, Not Golden | AAUP, accessed on September 3, 2025, https://www.aaup.org/academe/issues/fall-2022/american-higher-educations-past-was-gilded-not-golden

- The History of Grants: Part II - The Pursuit of Higher Education - USFCR Blog, accessed on September 3, 2025, https://blogs.usfcr.com/history-of-grants-part-2

- colleges and Universities - ResearchGate, accessed on September 3, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Sarfraz-Aslam/post/How_to_address_the_topic_the_effect_of_war_conflict_in_Yemen_on_the_education_of_the_postgraduate_Yemeni_students_in_China2/attachment/59f8434f4cde26d68ce5b6e8/AS%3A555455770357760%401509442383305/download/beko+2.pdf

- www.journals.uchicago.edu, accessed on September 3, 2025, https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/10.1086/342012#:~:text=Total%20enrollment%20jumped%20by%20more,Bill%20(Olson%201974).

- Why Is College So Expensive? 6 Reasons (and How to Make it Cheaper) | Earnest, accessed on September 3, 2025, https://www.earnest.com/blog/why-is-college-so-expensive

- Why College Is So Expensive - 4 Key Reasons - UoPeople, accessed on September 3, 2025, https://www.uopeople.edu/blog/why-college-is-so-expensive/

- Education Policy: Student Loan History - New America, accessed on September 3, 2025, https://www.newamerica.org/education-policy/topics/higher-education-funding-and-financial-aid/federal-student-aid/federal-student-loans/federal-student-loan-history/

- Do Student Loans Drive Up College Tuition? | Richmond Fed, accessed on September 3, 2025, https://www.richmondfed.org/publications/research/economic_brief/2022/eb_22-32

- Bigger’s Better? In Higher Ed’s Amenities Arms Race, Bigger’s Just …, accessed on September 3, 2025, https://jamesgmartin.center/2017/01/biggers-better-higher-eds-amenities-arms-race-biggers-just-bigger/

- Higher Education Finance - German Rectors’ Conference, accessed on September 3, 2025, https://www.hrk.de/activities/higher-education-finance/

- www.hochschulkompass.de, accessed on September 3, 2025, https://www.hochschulkompass.de/en/higher-education-institutions/higher-education-landscape/higher-education-funding.html#:~:text=Due%20to%20the%20legal%20framework,is%20provided%20by%20the%20states.

- Higher education funding in Germany - A distributional lifetime perspective, accessed on September 3, 2025, https://d-nb.info/1224884221/34

- Tuition Fees at Universities in Europe: Overview and Comparison for 2025 | Mastersportal, accessed on September 3, 2025, https://www.mastersportal.com/articles/405/tuition-fees-at-universities-in-europe-overview-and-comparison.html

- Higher education funding - France - Eurydice.eu - European Union, accessed on September 3, 2025, https://eurydice.eacea.ec.europa.eu/national-education-systems/france/higher-education-funding

- France’s Public Universities Face Funding Gap Despite Educating …, accessed on September 3, 2025, https://www.mindingthecampus.org/2025/08/06/frances-public-universities-face-funding-gap-despite-educating-majority-of-students/

- Tuition fees in France, accessed on September 3, 2025, https://www.campusfrance.org/en/tuition-fees-France

- Nordic Fields of Higher Education. Structures and Transformations …, accessed on September 3, 2025, https://www.nordforsk.org/projects/nordic-fields-higher-education-structures-and-transformations-organization-and-recruitment

- Full article: Academic freedom in Scandinavia: has the Nordic model survived?, accessed on September 3, 2025, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/20020317.2023.2180795

- Swedish higher education - Sweden.se, accessed on September 3, 2025, https://sweden.se/work-business/study-research/swedish-higher-education

- Exploring Free Universities in Europe for International Students - Crimson Education, accessed on September 3, 2025, https://www.crimsoneducation.org/us/blog/free-european-universities

- European Countries With Free College for 2025: Key Factors to Consider - Research.com, accessed on September 3, 2025, https://research.com/universities-colleges/european-countries-with-free-college

- What is Degree Inflation? | Goodwin University, accessed on September 3, 2025, https://www.goodwin.edu/glossary/degree-inflation

- Overeducated and underemployed: Why a diploma no longer guarantees success, accessed on September 3, 2025, https://www.marketplace.org/story/2025/07/29/why-a-college-diploma-no-longer-guarantees-success

- New Report: Degree Inflation Hurting Bottom Line of U.S. Firms, Closing Off Economic Opportunity for Millions of Americans - News - Harvard Business School, accessed on September 3, 2025, https://www.hbs.edu/news/releases/Pages/degree-inflation-us-competetiveness.aspx

- The Jobs and Degrees Underemployed College Graduates Have, accessed on September 3, 2025, https://www.stlouisfed.org/open-vault/2025/aug/jobs-degrees-underemployed-college-graduates-have

- Unemployment rates by Major : r/CollegeMajors - Reddit, accessed on September 3, 2025, https://www.reddit.com/r/CollegeMajors/comments/1lqgkik/unemployment_rates_by_major/

- The Most Unemployed Majors Today: What College Students Need to Know - Investopedia, accessed on September 3, 2025, https://www.investopedia.com/it-might-surprise-you-which-college-majors-have-the-highest-unemployment-rates-11774122

- College majors with the highest and lowest underemployment - Degree Choices, accessed on September 3, 2025, https://www.degreechoices.com/blog/majors-with-highest-and-lowest-underemployment/

- College Majors, Unemployment, and Earnings - CEW Georgetown, accessed on September 3, 2025, https://cew.georgetown.edu/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/Unemployment.Final_.update1.pdf

- Room for Progress in College Graduates’ Transition to the Labor Market, accessed on September 3, 2025, https://www.ppic.org/blog/room-for-progress-in-college-graduates-transition-to-the-labor-market/

- New report highlights growing skills gap and the need for stronger …, accessed on September 3, 2025, https://www.qu.edu/quinnipiac-today/new-report-highlights-growing-skills-gap-and-the-need-for-stronger-university-industry-partnerships-2025-02-20/

- Career Outlook for College Graduates in 2025 - Fastweb, accessed on September 3, 2025, https://www.fastweb.com/student-news/articles/career-outlook-recent-college-graduates

- More college grads are struggling in the job market. Here’s what NC students and experts are saying | WUNC, accessed on September 3, 2025, https://www.wunc.org/term/news/2025-05-23/college-grads-job-market-unemployment-underemployment

- Graduate Unemployment Hits Decade High As Traditional College-to-Career Pipeline Falters - Allwork.Space, accessed on September 3, 2025, https://allwork.space/2025/06/graduate-unemployment-hits-decade-high-as-traditional-college-to-career-pipeline-falters/

- Recent College Grads Bear Brunt of Labor Market Shifts - Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, accessed on September 3, 2025, https://www.stlouisfed.org/on-the-economy/2025/aug/recent-college-grads-bear-brunt-labor-market-shifts

- Why Are So Many College Graduates Unemployed in 2025? A Reversal of Expectations, accessed on September 3, 2025, https://www.davron.net/why-are-so-many-college-graduates-unemployed-in-2025-a-reversal-of-expectations/

- 10 Benefits of Having a College Degree, accessed on September 3, 2025, https://bachelors-completion.northeastern.edu/knowledge-hub/is-a-bachelors-degree-worth-it/

- Does Education Payoff? The Average Value of a College Degree | University of Cincinnati, accessed on September 3, 2025, https://online.uc.edu/blog/does-education-payoff-the-average-value-of-a-college-degree/